Lines of sight and light

Sunday | April 6, 2008 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

Two weeks ago the film critic and historian Paul Arthur died. (An obituary is here.) Apart from being a warm and robust man, Paul advanced our understanding of cinema in important ways. He was a committed teacher and an energetic writer. For years it seemed that almost every issue of Film Comment or Cineaste contained an essay by him. Although he had an encyclopedic knowledge of film, he wrote with particular brilliance about experimental work. His book, A Line of Sight: American Avant-Garde Film since 1965 (2005), reflects a lifetime of sensitive study.

Paul was naturally on my mind as I watched the avant-garde films on display here at the Hong Kong Film Festival. I’ve mentioned some in an earlier entry, but I wanted to signal others that seemed to me especially fine.

A set by Ben Rivers had quiet poetic overtones. Very short (We the People lasts only one minute), they center on landscapes. I especially liked House (2007), a spectral suite of images derived from a miniature house Rivers contrived.

Lewis Klahr‘s Antigenic Drift (2007) was a lovely and funny meditation on, I think, air travel in a post-9/11 age. Glossy images of airports are haunted by wandering bar codes, boarding passes, and anatomy drawings. Tablets burst out of blister packs and gather in colorful rank-and-file formations. The film bears the traces of Klahr’s visit to Wisconsin, some details of which are here.

Lewis Klahr‘s Antigenic Drift (2007) was a lovely and funny meditation on, I think, air travel in a post-9/11 age. Glossy images of airports are haunted by wandering bar codes, boarding passes, and anatomy drawings. Tablets burst out of blister packs and gather in colorful rank-and-file formations. The film bears the traces of Klahr’s visit to Wisconsin, some details of which are here.

Ken Jacobs is a legendary figure in the avant-garde. Prolific, outrageous, and wide-ranging in his interests, he has been at it for fifty years. His oeuvre includes the casually goofy Little Stabs at Happiness (1960), the epic Star Spangled to Death (1957-2004), and the classic Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son (1969). There Jacobs dissected a 1905 Biograph film on the optical printer (see P. S. below), revealing not only isolated faces and gestures in its crowded shots but also abstract masses of light and dark, and even the grain of the film stock.

Across several years, Jacobs and his wife Flo have developed a mode of multiple-projection performance. Their Nervous System shows films at different speeds, halts them, drops down filters, even superimposes slightly different frames from prints of the same film, creating vivid 3-D effects. Such spectacles trigger comparisons to nineteenth-century impresarios of wonder: the conjuror who calls up ghosts, the sideshow entertainer whose calliope happen to be a movie machine. (1)

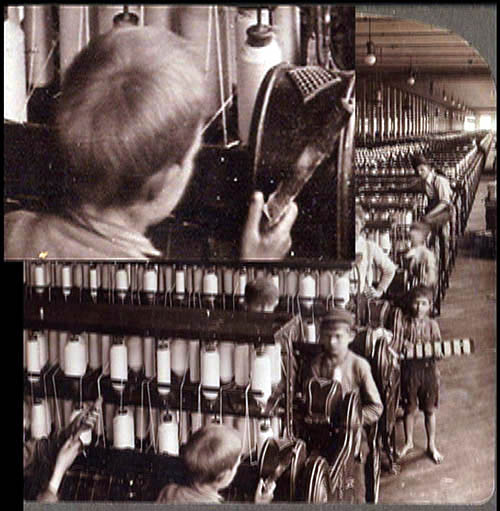

Capitalism: Child Labor (2006) might at first seem a rerun of Tom, Tom. A photograph shows men and boys at work in a thread factory. This dire image, with the workers’ flat expressions only adding to the sadness, might suffice in itself. But Jacobs takes the picture to pieces and shows us everything. He creates close-ups and long-shots, embedding them within one another to create games of scale. And then? Informed by Nervous System discoveries, Jacobs takes things a step further.

The picture originated as a stereoscope card. A stereoscope card consists of two side-by-side images, shot at angles corresponding to the difference between our eyes. Looking at the card through the viewer, the viewer has an illusion of 3-D. (Remarkably, my top illustration also features a factory scene.) For a detailed account of stereoscopy, see the Wikipedia entry.

Jacobs intercuts the two slightly different photos, often allotting only a single frame to each. With simple geometric shapes this procedure would yield “wiggle stereo,” as illustrated in the Wikipedia piece. But the density of the images evidently allows Jacobs to create a fluttering, nagging sense of volume. We seem to move just a bit around the figures and their workstations before popping back to our starting place, then launching again, endlessly. Somehow my brain thinks I’m spasmodically starting to circle through the factory.

This is why we’re right to call such films experimental. They often try to discover how our senses, our minds, and our emotions reveal themselves in their encounter with cinema. The goals are different, I grant you: Art exposes, science explains. But scientists should have a special eagerness to study avant-garde films. I can’t imagine anyone interested in filmic perception—and not just cognitivist film researchers—who wouldn’t find Capitalism: Child Labor a provocation to marvel at how our vision jumps to conclusions about depth. This movie makes us say Wow.

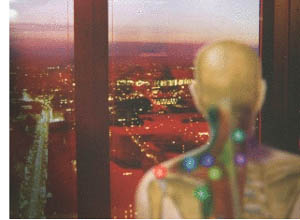

Song and Solitude, a 2006 film by Nathaniel Dorsky, was simply stunning. (2) In the Brakhage tradition, it’s woven out of lyrical shots of details seized and abstracted. Reflections, silhouettes, out-of-focus textures, veils and grids shedding unexpected ripples of light: everything seems radiant. Sometimes you recognize a familiar object, like a window screen pebbled with rain. Often, though, you have to ask: What am I seeing? And then Why don’t I ever notice this?

Dorsky’s Buddhist-influenced aesthetic, revealed in his book Devotional Cinema, drew this commentary from Paul Arthur:

Old School doesn’t describe it. Dorsky has achieved such a subtle mastery over the most basic means of cinematic expression–composition, duration, juxtaposition–that he can squeeze a wealth of emotional vibrations out of the silent, seemingly banal interplay of foreground and background objects. A formalist with a brimming, elegiac soul, Dorsky will gently rock your attitude toward cinematic landscape. His world is a sublime mystery measured by patience and unmatched visual insight.

I didn’t know Paul well. I met him around 1974, when we had a good conversation about landscape in Anthony Mann. We ran into each other occasionally over the years and corresponded a little.

His generosity to Kristin and me came through on several occasions. In a roundtable discussion published in October no. 100, he called attention to the fact that Film Art tried to remind students and teachers of the importance of avant-garde film. (3) In reply to an essay of mine in Film Quarterly, he sent overabundant praise but added several pointed questions that forced me to tighten up my argument. Most vividly, when I was criticized (some would say personally attacked) in the pages of Film Studies’ most prestigious academic journal, he was moved to write me with encouragement. Of my critic he wrote: “To hell with him if he can’t take a joke.”

Like a great many others, I will remember Paul with affection and admiration.

Song and Solitude.

(1) An engrossing interview with Jacobs can be found here.

(2) By the sort of coincidence I like, Song and Solitude also played the Wisconsin Film Festival, which I had to miss this year. Trusty Joe Beres of the Walker Art Center, still a Badger at heart, provides coverage.

(3) The discussion is here, but beyond the first page the material is proprietary.

P. S. 21 May 2009 Keith Sanborn wrote me to point out that, in a reply to Ed Halter (who discusses Anaglyph Tom (Tom with Puffy Cheeks) in Artforum), Ken Jacobs corrects the frequent claim that the 1969-71 Tom, Tom was made on an optical printer. No, says Jacobs; he rephotographed the movie from the screen. Here is the inimitable explanation Jacobs supplied to Halter.

The movie so pushes forward the character of film projection. Images explode out of darkness. Nor was I using a specialized analytic projector that with a steady flicker minimizes exchange of frames. I used what had been a common RCA home sound-projector, from the 1940’s, possibly the late 1930’s, but one with a hand-controllable clutch that allowed for slowing and even stopping the film. Freezing as it’s called but usually more like burning. A heat-shield would fall in place to protect the film from burning but would then darken the image, and so I removed it and took my chances with burning. The energy that is light was a featured and constant presence in the work. Darkness is death and the old reclaimed images constantly struggle against death to proclaim themselves. Release of energy, via intermittent projection or in the return of rambunctious ghost-actors, was much of what the work was about.

Thanks to Keith for calling my attention to this.